Ceremony as Story

"The universe is made of stories, not atoms." --Muriel Rukeyser

The language of decolonialism, comes from Indigenous scholarship and argues that colonization never ended. Postcolonial language is concerned with the people and places that were under colonial rule, are no longer colonies, but are continuing to experience the ongoing impact of colonialism. What keeps me up at night, is wondering what we are supposed to do about colonial thinking that leads us to enact harm upon one another? Especially when the harm lead us to silence, marginalize, or even worse, kill one another? Some have said that simply decolonizing is not enough to remove the underlying thinking upon which colonial worldviews are built. Audre Lorde writes about the master’s tools not being able to take down the master’s house. What if the words decolonial and postcolonial are the master’s tools?

Oppression is never simple — its meant to be complicated and confusing. Love on the other hand is quite simple. So simple, it’s elegant. We all are deserving of love. I wonder why this is so hard to believe in? Perhaps in order to shift our worldviews, we need new stories about love, about each other. Indigenous story work considers the relationship between the participants living the story, the person telling the story, and the story itself. There’s an important connection between Indigenous story work and relational accountability. It offers a wonderful critique to a western myth that the individual must be objective in order to successfully determine truth of the matter. In this way, I might suggest that Indigenous story work has a social justice outcome that could influence the way we think and as a result, the way we treat each other. Indigenous story work might offer a reminder that “the world is made of stories.” David Loy might say, “turtles all the way down.”

For rationalist scientists, the world is composed of factual data. But story acknowledges that a fact is discovered and accounted for because the story makes those facts meaningful. Stories offer an accounting of relationships that co-emerge in different locations and situations, and as such, produce new stories together, in relational care and accountability for one another. Stories offer both the storyteller and the listener a moment to shape the content and the process of coming to know. Shawn Wilson says that story is a ceremony.

According to Gregg Castro, ceremonies are alive, and are entities that exist. We don’t own them, rather they live on because we live in and within them. Castro, like Wilson, is saying that ceremony is a being that requires tending to in order to build relationship with. Just to compare, a western rationalist worldview informs me that ceremonies are tools to be used. But what if Castro is right? What if ceremonies are alive and exist because of the relationships that create them and exist within them? What stories might we begin to create together?

Re-storying

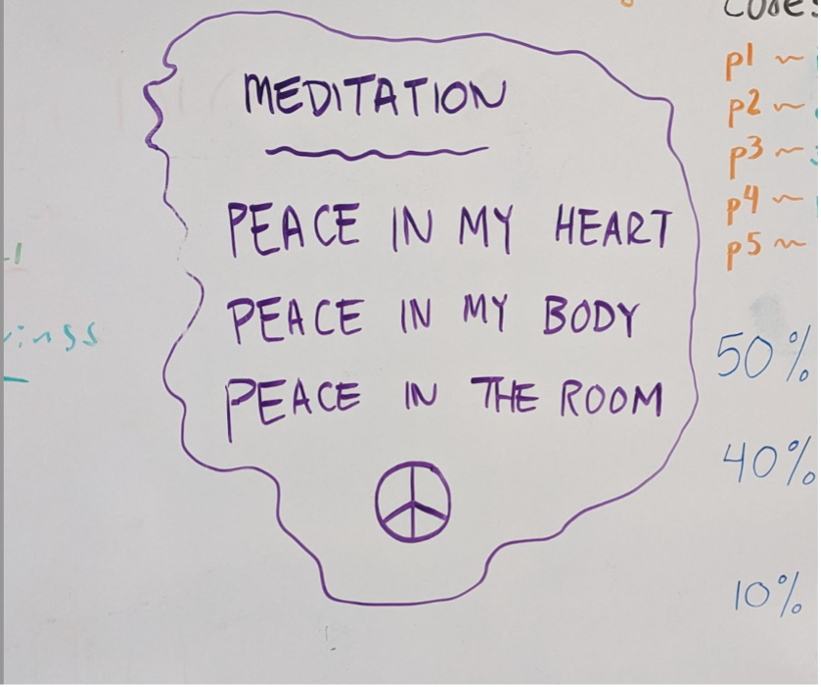

A friend of mine went to work one morning to the high school where she teaches and offered a meditation to her students. It was a meditation born out of a weekend in ceremony.

She brought it to the classroom and to her students as a way of helping them to connect with peace. She shared that the meditation is intended to connect with others. By starting with peace in the heart, she hoped her students could grow peace in the body, and as a result, peace could become a part of the space of daily interaction and engagement within the classroom.

Every day, I become more curious about how healing and story work together. I suspect that as we learn together, we also create possibilities for healing our world together. Western stories are mostly framed in isolation. For example, when I am ill, I go to the doctor and take a pill to get well. In this way, illness is a symptom of me, an isolated individual, whose healing occurs alone, in quarantine. Exploring another perspective, Indigenous ontologies are framed in relationship. For the Shipibo, a community of Indigenous people who live in the Amazon rainforest in and around Peru, illness occurs when one is out of right relationship. And healing comes as a result of righting the relationship.

Indigenous knowledge makes me think about the colonial efforts of the United States and the mindset of the rugged individual who sources strength from within to combat the world outside. As a westerner situated on unceded land in Ohlone territory, I think about stories of categorization and separation stitched and nestled into colonial worldviews.

More recently, I have been thinking about how colonial structures get in the way of our efforts to deepen relationship with non-human and more-than-human beings.

In the last decade, a modern movement has emerged once again around the consumption of entheogenic plants. One might see this as a renaissance through which the political, social, scientific, and spiritual revival of psychedelic exploration is re-emerging within the context of a Euroamerican neoliberal, and countercultural movement. Using the language of psychedelic renaissance, I am inclined to better understand the exploitative endeavors of the European Renaissance. A time known in part, for the religious expansion of the Catholic Spanish missionaries who sought to colonize and exploit the western world. The European Renaissance is often recounted as a prolific time for European art and literature during the 14th – 16th centuries. While aspects of this perspective may be true, this view tends to neglect the struggle of the Indigenous communities who were exploited as a result of the missionizing efforts in the Americas. In search of power associated with new knowledge, resources, and labor, Spanish encounters with American cultures in the West were brought back to Europe and translated through the political structures and cultural norms of European religious thought at the time.

Focusing on the exploits of the Spanish missionary encounters, Daniel Fogel describes a kind of colonial theology that emerged during the European Renaissance which he names, enslavement theology. Fogel demonstrates how early encounters between Spanish missionaries and Indigenous communities was driven by an imperialist desire for power and a desire for subjugated bodies to help conquer new lands. The Spanish missionaries, after having fought the past 700 years in a ping-pong battle with the Arabs for control of Spain, were accustomed to missionizing the peasant class in preparation for fighting the next uprising.

This process of missionizing, or enslavement theology, included indoctrinating the working poor with religion and notions of freedom while offering food and shelter. After a final winning battle for Spain at the end of the 15th century, Catholic missionaries traveled to the Americas with a well honed practice of enslavement theology. Fogel describes how this thinking is what led the Spanish to commit genocide and cultural oppression upon the Native Americans living along the western coastline in both North and South America.

Fogel’s story of colonialism, religion, and the European Renaissance is another way to understand the historical events of the European Renaissance as well as the current day colonial nature of universalizing epistemic frameworks that inform what we know and how we know what we know. His re-writing and re-storying of history through Indigenous story work, helps to shed light on the importance of deconstructing dominant, hierarchical epistemologies, and ontologies that construct historical meaning.

Connecting the European Renaissance with the Psychedelic Renaissance, uplifts a question, who is benefiting right now?

As was discovered through Fogels story, the European Renaissance was great for Europeans but not so great for the Indigenous communities who were exploited and colonized and suffered under the impact of an ongoing genocide. During this modern psychedelic renaissance, Indigenous elders speak of an encroachment into their wisdoms once again. How do western entheogenic spiritual seekers not make a similar turn toward the destruction of culture, land, people when the popular western frame of domination remains in the psyche of so many entheogenic spiritual seekers in the United States today?

What I'm curious about is how do we trouble colonial assumptions that encourage meaning making from the consumption of entheogenic plants in spiritual and religious settings?

As I think about “right relationship” I’m reminded of “good relationships.” What is good anyway?

What exactly does it mean to consume and share sacred plant medicines in a good way? Is this even the right question to ask? Perhaps there is no answer. I imagine Báyò Akómoláfé, author, teacher, healer-trickster, and traveler between liminal fault lines and fissures might say, “good” is knowledge under construction. I imagine he might explore the word “good” as simply a gesture or an idea that might move one to trouble the word, and to ask even more questions about how to be in relationship with the more-than-human and non-human worlds. And not just during ceremony, but all the time.

I struggle with the word good because the number of different groups of people, who come from different histories, who are informed by any number of trajectories, and are rooted in various territories, may come to understand this word differently. To complicate things even further, different plants like peyote, mushrooms, iboga, and ayahuasca all come from different socio-cultural contexts. The diversity of each situated group, along with each plant, and the spirits that travel, means there are differing ideas of social justice and varying interpretations on words like race, ethnicity, cultural appropriation, Indigenous, Native American, first peoples, shaman, and of course, the word, good.

So, I return again to the words, colonialism and decolonialism. I recently read a piece in the Atlantic, The Decolonization Narrative is Dangerous and False by Simon Sebag Montefiore. Usually I can spot problematic articles quickly, but this one got me for a moment. So much so, that I thought I might align with Montefiore’s ideas. Before explaining what happened, I’ll first take you to the end of the story with a final analysis of the article: The author does not declare his standpoint like a good scholar, and he legitimizes Israel’s actions and condemns Hamas without context. I am reminded once again that an aspect of misusing of power is to publish articulate and well-written articles that suggest factual objectivity without accounting for the relationships that make those facts meaningful. In short, Montefiore’s article is a hegemonic demonstration of power misused to support the powerful.

But back to why I was temporarily confused by Montefiore’s words. I recently learned about Nego Bispo, a Brazilian philosopher. As an Indigenous person who has survived colonization, he does not seek decolonization.

In fact, he asked God to protect him from both colonizers and decolonizers alike.

Refusing to play the colonizers game, Bispo preferred the language of counter-colonization.

I think Bispo’s point is that decolonization is for the colonizers, not the indigenous people who are suffering under the long-lasting effects of colonization. So, when I read Montefiore’s title, “The Decolonization Narrative is Dangerous and False” I immediately thought of Nego Bispo. But what’s dramatically different between the two writers, is their positionality. From Bispo’s lens, the language of decolonization is also the removal of a colonial mindset. As an Indigenous man, Bispo does not need to remove a colonial mindset, he is suffering from underneath it. Montefiore, on the other hand, is currently benefiting from colonization. Removal of decolonial language only serves to benefit Montefiore and others who think like him. From this lesson I have to say that one’s worldview is essential to interpreting colonial and decolonial language.

For Bispo, the word, decolonization is an academic theory, not a way of life. He says that the prefix “de-” means the removal of something. From this lens, decolonization is something that is for settler colonial people – the removal of an oppressive way of being, knowing, thinking, and doing. If I attempt to gaze at colonial and decolonial language from an Indigenous lens, I can see how the binary framing is problematic. How does one “remove” colonial actions when the land has already been stolen, or the bombs have already dropped, and the people are already dead? There is no way to undo what’s been done. Perhaps instead, the only next step is through – to begin re-constructing, re-storying, and re-imagining.

So, when I talk about the words and the framing of colonialism and decolonialism, I suppose I’m highlighting a cautionary tale. That colonizers not to get too comfortable with the notion of removing a past that cannot be removed.

Perhaps stories are not meant to be deconstructed, only reconstructed, and told again.

And if we are to shift into a new paradigm of thinking, then the idea that there are only two options – one with a colonial view and one without, needs to be interrogated.

More recently a close friend and schoolmate asked me as I was questioning what it means to decolonize ceremony, "If colonizing is the problem, then why start with it? Why not start with a ceremony that is Indigenous and explore what that means?" To her point, a trick of decolonization is the deterritorialization of the practice. She's wondering if it is even possible to create an Indigenous ceremony away from its place of origin. She’s got a point. However, if I walk away from the decolonization question, I’ve left a much needed conversation about how to shift a worldview that has been engrained in me for generations.

Indigenous wisdoms have helped to trouble and call into question colonial belief systems, like the belief in a natural divide between human/nature, mind/body, and spirit/human. It is a belief in divisions like these that have kept me separated and prevented me from exploring more nuanced perspectives like Bispo’s. His inquiry and even distaste for the word decolonialism is a reminder that the act of decolonizing could simply be yet another binary and therefore reactionary response to colonialism – dualism rising out of the ashes once again.

I’ve seen a number of Instagram memes about the anti-shaman and even the anti-fake shaman.

I’m troubled because even these memes are overly concerned with simply righting a wrong. They appear to be more shallow covers that showcase what it means to oppose colonial power. At the very moment, I’m wondering if the many western decolonizing debates I've engaged in are just more arguments that support a “move to innocence” or are arguments that show moral culpability and signal that I identify with decolonial attitudes and metaphors? And all the while, as I debate, too many people are suffering under violent ongoing settler nativist efforts, and our earth is still in serious disrepair.

Robin Wall Kimmerer writes in her book, Braiding Sweetgrass about a time when she was teaching. She asked her students to name a positive impact that humans have had on the environment. Not one of her students could answer. It made me think about my own belief system of humans and the natural world. Her story asked me to confront my own hidden narrative about humans being the scourge of the earth. If I look outside western narratives, I can find regenerative relationships involving humans, with non-humans, and more-than-humans. Being in ceremony with plants means being in a relationship with those plants, those spirits, those humans in the room.

For Kimmerer, relationship is key. She wrote, “[W]e can’t meaningfully proceed with healing, with restoration, without ‘re-story-ation.’ Our relationship with the land cannot heal until we step into a different story, which re-orients us to other beings and the environment we share, and changes how we relate to them.”

Like Kimmerer, Indigenous elders around me are constantly reminding me about relationship.

I think this is why there is no one route to decolonizing our lives together. It takes relationship and relationship takes an adventure out into the unknown to build coalitions together.

If I think about processes and situations that bring me into relational accountability with the plant spirits found in the ayahuasca brew, I think about the Shipibo family in Peru I have come to know and love, who grow vine and leaf on their land. I think about the Shipibo women in Pucallpa and their journey through colonization and genocide brought on from settler missionaries wishing to convert them – a practice that is still happening today. I’m reminded of the revitalization of the Shipibo culture and language and how, in part, that has come from economic investment by people in the Global North interested in learning about ayahuasca and spirituality. And I’m reminded that the buying and selling of ayahuasca experiences at retreat centers in the Amazon rainforest is also layered with its own set of exploitative ills and colonial endeavors aimed at commodifying God.

Emerging from Gregg Castro’s talk on Native Sovereignty, I now treat ceremony as an entity to be in relationship with. Shifting my worldview, I understand more deeply how healing occurs within the context of relationship and community.

Maybe healing does not occur in isolation but only when we find the edges of ourselves bumping into the edges of another.

I started writing this essay from a first-person perspective as a way of struggling with what it means to tell stories. The interesting thing in all of this writing is that I’m dissolutioned by the first-person narrative. A first-person accounting only exists because of story and story only exists because there is someone to tell it to and someone to create it with. In other words, the “I” comes into shape and existence because of the “we.”

If writing is a process of coming to know, I have come to understand that mycelial connections – thread like roots that that twist and tangle and feed one another underground – are a great metaphor for Indigenous story work. The distinction between posthumanism and Indigenous research is an important nuance. I imagine that posthumanism begins with the objectified glory of the individual tree, while Indigenous story work begins with community of interlocking root systems feeding and thriving upon one another. Even though I come from a posthumanist lens which often attempts to center the metaphor of the hero’s journey, I intend to share stories that re-imagine the world from the many connections underneath the forest floor.

Stories built on stories questions the notion of a master-story – a final, or ultimate story that explains all other stories. Loy reminds us that “it’s turtles all the way up too.” The one grand story cannot even see itself enough to explain the relationship between the story and the stories outside itself.

Though our stories may be imperfect, perhaps we’ll know they are successful when the health and wellness of all the communities in and around us are improving.